The author produces this graphic to illustrate the point.

Mortality is falling in most countries, often far faster than the 4.4% per year that is the millennium development goal (MDG). This is good news of course, but there is another health trend underway that seems to indicate that the children who are avoiding mortality in youth are most likely to succumb to diseases in the prime of adulthood. The source of these illnesses will likely be non-communicable diseases (NCDs) such as diabetes, cardiovascular disease, and respiratory problems—threats that are usually associated with the lifestyles found in more-developed countries.

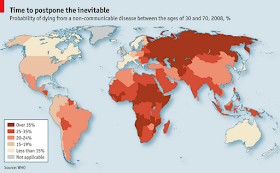

Another article in The Economist provides this graphic:

The point being made is that in the developing world, the threat of non-communicable diseases is large and it is growing. It is also interesting to note that the United States, even though it spends much more on healthcare than any other country, does not make it into the rank of "developed" countries via this metric.

Thomas J. Bollyky provides an article in Foreign Affairs that addresses the global issues associated with NCDs: Developing Symptoms: Noncommunicable Diseases Go Global.

Bollyky describes the situation with NCDS as an epidemic.

While progress is being made in combating infectious diseases and the causes of childhood mortality, the overall healthcare systems in many countries cannot keep up with the problems being encountered in adulthood.

Bollyky tells us that this is not only a problem for the individual countries; it is a major threat to global economic development as well.

"According to the World Economic Forum's 2010 Global Risks report, these diseases pose a greater threat to global economic development than fiscal crises, natural disasters, corruption, or infectious disease."

Bollyky also provides a different perspective on the data of the previous chart.

"NCDs that are preventable or treatable in developed countries are often death sentences in the developing world. Whereas cervical cancer can largely be prevented in developed countries thanks to the human papillomavirus vaccine, in sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia, it is the leading cause of death from cancer among women. The mortality rate in China from stroke is four to six times as high as in France, Japan, or the United States. Ninety percent of children with leukemia in high-income countries can be cured, but 90 percent of those with that disease in the world's 25 poorest countries die from it."

He follows up with this prediction:

The WHO predicted back in 1996 that the health issues associated with NCDs were a problem for developing countries and would soon dwarf concerns about infectious diseases. However, there has been little appetite for action.

Concern has now been raised to a level at which it was possible to generate a meeting at the UN General Assembly last September. Little emerged from that meeting other than pronouncements. There were the expected constraints on funding in a weak economy, and the lobbying efforts of those who benefit from helping create illnesses, but Bollyky blames the lack of progress on a strategic problem.

"Trying to address these diseases as a single class and on a global level has both broadened opposition and diffused support for effective action. On one hand, addressing NCDs as a single category has united a wide array of otherwise disconnected industries, from agriculture to pharmaceutical companies and restaurants, against global targets to reduce NCDs and their risk factors. On the other hand, it has made it difficult to mobilize states and sufferers of NCDs worldwide around a specific and meaningful policy agenda."

Bollyky suggests focusing on a few high payoff approaches with attainable goals.

There are efforts in place in some countries to regulate and discourage tobacco use. These should be extended to all developing countries. Success with tobacco could lead to similar regulations and controls on the intake of alcohol, salt and trans fats.

The collaboration of the advanced countries would be required. While they think it is appropriate to discourage tobacco use in their own lands, they seem willing to encourage its use in other countries.

The international community can do much to address this issue, but, ultimately, the responsibility lies with the developing countries themselves. Just as better governance led to the improvements is child mortality mentioned at the beginning, better governance will be required to address the more subtle issues associated with NCDs.

This last conclusion applies as well to the developed countries.

No comments:

Post a Comment