An article in The Economist provides some basic data on hospital costs by comparing average costs per day in hospitals in a variety of countries.

The explanation for why US costs are three to ten times higher than those in other developed countries is quite simple.

The outrageous charges have already caused patients and other providers to try to limit hospital stays. This has eliminated any significant growth in hospital admissions in recent years. Many people thought that Obamacare would be good for hospitals as it provided healthcare insurance to millions more people, but that may not be the case.

The goal of Obamacare is to fundamentally reform the process by which healthcare is delivered. It is not doing this by fiat, but rather by offering financial incentives for providers to produce less expensive and more effective care. These incentives are built into Medicare, a program big enough to generate paradigm shifts throughout the medical industry.

The Obama administration has also shed light on the prices hospitals charge for services by publicizing their price lists. Elisabeth Rosenthal provided an excellent article on hospital costs in the New York Times for those interested in the details.

One of the reasons why hospital pricing is unconnected with reality is because hospital costs are determined by relatively inflexible expenses. A given hospital has to be able to cover whatever costs are residual from obtaining the land, building the structure, and filling it with the required equipment. The facility must be staffed with doctors, nurses, technicians, and various workers. The hospital does have some leeway in staffing levels, but if you build a 100 bed hospital, you better have access to enough people to care for the case where all 100 beds are occupied.

So if you spend a night in the hospital, blow your nose while in your room, and discover you have been billed $25 for tissue, that should not surprise you. Hospital costs have very little to do with services rendered. Yearly costs must be covered whether there are patients or not. Since patients are the major source of revenue, they must be charged whatever it takes to meet the expenses of the facility.

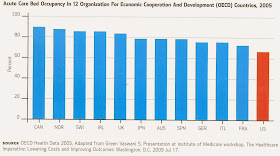

Hospitals have had little incentive to skimp on expensive features because they have always been able to raise their prices as needed. This has allowed numerous inefficiencies; perhaps the greatest is that hospitals have outgrown the demand. There are more hospital beds out there than are needed, and someone has to be charged for those excess rooms whether they are filled or not. This article discussed the issue and presented this chart of average hospital occupancy for a number of countries.

Note that the figure for the US is at about 65%, while other countries provide effective healthcare at occupancy rates of close to 90%. If we have hospitals with an occupancy rate of 65 percent when 90 percent is an attainable goal, then we have about 25 percent more hospital beds—or hospitals if you wish—than we need. We, as patients, are being overcharged to support that excess capacity.

If significant price pressure is placed on hospitals, it is hard to see how they can cut expenses without also cutting excess facilities.

While it is true that our hospitals are capable of providing the best medical care available, often they don’t. Very, very often they don’t. This article discusses recent estimates of how many patients are killed or hurt by avoidable medical errors in hospitals. The number of people who die because of faulty care in hospitals was estimated at an astonishing 440,000 per year. And ten times more are harmed by improper care. This makes the mere act of being admitted to a hospital the third largest cause of death in this country!

Another way to view these numbers is to consider that the death rate is 1205 per day. That is about equivalent to having four large commercial aircraft crash every day. Can you imagine what would happen if four aircraft crashed in a single day? The entire industry would be shut down indefinitely. Yet business goes on as usual in our hospitals.

All of this shoddy care is certainly tragic for those affected, but it also comes with an economic cost. Physicians and insurance companies have become more cost-conscious, and are coming to recognize that hospitals are part of the problem rather than part of a solution. It is becoming clear to many that hospitals are for use only when there is no alternative.

An article by John Tozzi in Bloomberg Businessweek discusses some of the trends that have emerged as healthcare providers experiment with accountable care organizations (ACOs).

Results of this switch to ACOs are beginning to emerge.

"ACOs have achieved those savings in part by doing something the law didn’t anticipate: excluding hospitals from their groups….more than half of ACOs are led by doctors’ practices and leave out hospitals entirely."

And why might that be?

The goal of basing remuneration on quality of services rather on number of services appears to have had an effect. A person who needed chronic care in the past was a cash cow for the medical community. Now it is recognized that it is more economical to spend more time and effort to bring that patient to a state where less medical attention was needed. What does this imply for the future of hospitals?

Jonathan Rauch provides insight into how Medicare patients have been treated by healthcare providers and how greater savings can be attained. He has produced an article in The Atlantic: The Hospital is No Place for the Elderly.

Rauch points out that longer life spans have changed the healthcare needs of our aging population. As people live longer they acquire not only significant medical problems, but multiple significant problems.

"Seniors with five or more chronic conditions account for less than a fourth of Medicare’s beneficiaries but more than two-thirds of its spending—and they are the fastest-growing segment of the Medicare population."

These people are not going to recover from their medical ailments and they need frequent medical attention, but not the kind of intense but cursory assistance they receive in emergency rooms.

Hospitals are dangerous for all people, but particularly for the elderly.

Rauch examines other models for the care of the frail elderly. One example he describes is an organization called Hospice of the Valley that operates in Phoenix, Arizona.

This effort was run mostly on funds from charitable contributions and research grants. That is no longer the case.

This is a model for care that even hospitals are beginning to turn to. Sutter Health, a large network of hospitals and doctors in Northern California, has been experimenting with a program it refers to as Advanced Illness Management (AIM) that is similar in philosophy and execution to that of Hospice of the Valley.

Why is an approach likely to limit hospital admissions of interest to a hospital chain? Rauch provides this comment:

The Sutter strategy seems to be Darwinian: if only the fittest hospitals are going to survive, then we better aim to be among the fittest.

For three straight years the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) has had to decrease its projected Medicare and Medicaid costs. The net savings to the government from these changed projections adds up to $135 billion for the year 2020 alone. Change is here and more is coming; Obamacare is part of the solution, not part of the problem; and it is going to be a scary ride for some people in the medical community.

No comments:

Post a Comment