Russia’s determination to regain control of former Soviet Union countries is driving the world to a dangerous place. Its accommodations with China, which also has plans for regional, if not worldwide domination, is particularly troubling. Understanding the characteristics and future possibilities of Putin’s domain is useful in evaluating how practical his goals are. Russia’s economic prospects were considered in What Does the Future Hold for Putin and Russia?. The nation seems cursed by an abundance of natural resources that precludes the development of a balanced economy capable of thriving in the warmer world which is coming. Long-term developments are not promising. Here Russia’s bizarre demographics will be discussed.

Russia is a huge country with a relatively small population—one with a rather unique history. Centuries of serfdom with aristocratic overlords was followed by the violent disruption of a world war, the communist revolution with its economic disruptions, another world war, the failure of the Soviet Union and subsequent economic chaos, and finally a remake of the tsarist-like system with Putin as the supreme leader surrounded by billionaire cronies as the new aristocracy. Nicholas Eberstadt provided a look at the state of Russia’s population of 2011 in a Foreign Affairs article: The Dying Bear. The occasion for his article was the twentieth anniversary of the end of Soviet Russia.

“For Russians, the intervening years have been full of elation and promise but also unexpected trouble and disappointment. Perhaps of all the painful developments in Russian society since the Soviet collapse, the most surprising -- and dismaying -- is the country's demographic decline. Over the past two decades, Russia has been caught in the grip of a devastating and highly anomalous peacetime population crisis. The country's population has been shrinking, its mortality levels are nothing short of catastrophic, and its human resources appear to be dangerously eroding.”

“Globally, in the years since World War II, there has been only one more horrific surfeit of deaths over births: in China in 1959-61, as a result of Mao Zedong's catastrophic Great Leap Forward.”

“By various measures, Russia's demographic indicators resemble those in many of the world's poorest and least developed societies. In 2009, overall life expectancy at age 15 was estimated to be lower in Russia than in Bangladesh, East Timor, Eritrea, Madagascar, Niger, and Yemen; even worse, Russia's adult male life expectancy was estimated to be lower than Sudan's, Rwanda's, and even AIDS-ravaged Botswana's. Although Russian women fare relatively better than Russian men, the mortality rate for Russian women of working age in 2009 was slightly higher than for working-age women in Bolivia, South America's poorest country; 20 years earlier, Russia's death rate for working-age women was 45 percent lower than Bolivia's.”

What is it about Russia that produces these results? Eberstadt had no simple answer.

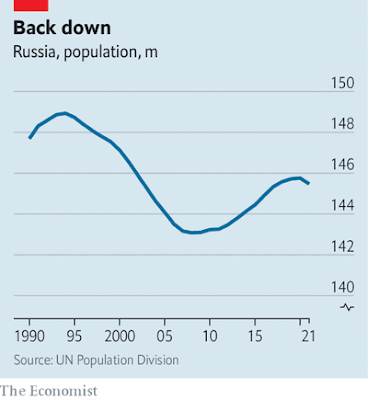

A recent edition of The Economist provided both an update and a possible explanation for Russia’s demographic woes. One article, Russia’s population nightmare is going to get even worse, provides new data. Consider the change in Russia’s population over time.

The population was plummeting in the decade before Eberstadt’s article, but it then turned upward before again beginning to fall in recent years. That is not a sign that something significant had changed. Social rewards for having more children helped increase the number of births but, at best, births and deaths were about equal over a several year period. The population growth came mostly from immigration from surrounding countries. A plot of births and deaths over the years is more informative.

The population loss between 1990 and 2010 was clearly a significant occurrence. Government policies increased the birthrate temporarily but policy changes, the pandemic, and war are driving the death rate sky high.

“A demographic tragedy is unfolding in Russia. Over the past three years the country has lost around 2m more people than it would ordinarily have done, as a result of war, disease and exodus. The life expectancy of Russian males aged 15 fell by almost five years, to the same level as in Haiti. The number of Russians born in April 2022 was no higher than it had been in the months of Hitler’s occupation. And because so many men of fighting age are dead or in exile, women now outnumber men by at least 10m.”

To the remarkable tendency of Russian people to die at an early age has been added the war deaths and the flight of young people to avoid military service. Russia’s population is becoming older and more enfeebled.

“According to Western estimates, 175,000-250,000 Russian soldiers have been killed or wounded in the past year (Russia’s figures are lower). Somewhere between 500,000 and 1m mostly young, educated people have evaded the meat-grinder by fleeing abroad. Even if Russia had no other demographic problems, losing so many in such a short time would be painful. As it is, the losses of war are placing more burdens on a shrinking, ailing population. Russia may be entering a doom loop of demographic decline.”

“The decline was largest among ethnic Russians, whose number, the census of 2021 said, fell by 5.4m in 2010-21. Their share of the population fell from 78% to 72%. So much for Mr Putin’s boast to be expanding the Russki mir (Russian world).”

The impact of the pandemic on Russia is indicative of a nation whose leader can’t or won’t provide his people with healthcare.

“The Economist estimates total excess deaths in 2020-23 at between 1.2m and 1.6m. That would be comparable to the number in China and the United States, which have much larger populations. Russia may have had the largest covid death toll in the world after India, and the highest mortality rate of all, with 850-1,100 deaths per 100,000 people.”

The article finished with this summary.

“The demographic doom loop has not, it appears, diminished Mr Putin’s craving for conquest. But it is rapidly making Russia a smaller, worse-educated and poorer country, from which young people flee and where men die in their 60s. The invasion has been a human catastrophe—and not only for Ukrainians.”

That article also provided no explanation for Russia’s fundamental high mortality rate that is independent of pandemic and war losses. In the same issue, The Economist also pondered a comparable problem in England. Its mortality rate has been steady or increasing rather than falling as it has for decades. The effect is not as dramatic as in Russia, but it is cause for concern and demands an explanation. The article was titled Why did 250,000Britons die sooner than expected? That number is the increase in deaths over the last decade beyond what can be explained by taking factors like the pandemic into account. The discussion points to a simple reason for increased mortality.

“As for where people are dying, the uncomfortable truth is that the 250,000 do not die in places like the London borough of Westminster (where life expectancy surpasses that in the Swiss canton of Geneva). They die in poorer towns and cities.”

An interesting claim is made about the quality of healthcare and increased mortality rates.

“A government press release in 2021, to mark the creation of an Office for Health Improvement and Disparities, acknowledged that around 80% of a person’s long-term health is determined not by the care they receive but by wider social factors. Cold, damp homes can increase the risk of developing heart and respiratory diseases. A low income or a limited education can worsen the choices a person makes about their diet. Poor people sometimes use food, drugs and gambling as an escape.”

The concept of a “level of deprivation” is introduced to characterize population groups and assess mortality rates.

“Outside London, there is almost a perfect correlation between life expectancy in a local authority and its level of deprivation—as measured by a government index of a battery of economic and other factors. Our calculations also suggest that between 2001 and 2016 income and employment deprivation alone accounted for 83% of the variation between local authorities in life expectancy.”

The austerity policies of the ruling party over the last decade is blamed for the excess deaths.

“During the 2010s, spending per person decreased by 16% in the richest councils, but by 31% in the poorest. Benefits were also cut. Our analysis of a detailed dataset of local government spending from 2009-19, compiled by the Institute of Fiscal Studies, a think-tank, shows that places with the largest relative declines in adult social-care spending and housing services were the ones that suffered the greatest headwinds to life expectancy.”

It has long been known that stresses generated by economic worries, a lack of dignity, a feeling of being unequal and other issues can generate ill health. Psychologists know this, but politicians seem to refuse to consider it. What these English researchers are saying is that a government that does not provide the social needs of a section of population will cause adverse health outcomes—such as early death. Consider the English town of Middlesbrough where class differences lead to longevity drops as extreme as those found in Russia

“…in Middlesbrough, the gap in life expectancy between the richest and poorest fifth of the population is 11.3 years for men and 8.8 years for women.”

If such effects are measurable then an explanation for

Russia’s early deaths lies in concluding that Russia has a lousy government

that does not provide for its social needs.

Can anyone doubt that is true.

No comments:

Post a Comment